solidarity

under repression

a comprehensive study

of russian civil society

based on data from 2024

about the study..............................................................................................................................>>

data and methods..........................................................................................................................>>

detailed findings.............................................................................................................................>>

map of Russian civil society at the end of 2024..............................................................>>

analyzing the digital footprints of civil society work.....................................................>>

the challenge to civil society: political pressure............................................................>>

the challenge to civil society: lack of resources.............................................................>>

the challenge to civil society: communication difficulties.........................................>>

conclusion.........................................................................................................................................>>

bibliography and references....................................................................................................>>

115 in-depth interviews were conducted with representatives of various initiatives

-

15 focused on trends in civil society in general

-

100 focused on the status of specific initiatives

12 online communities were studied through digital ethnography.

4 offline and 5 online conferences were examined using ethnographic methods.

6,500 online communities (Telegram and VK) were analyzed quantitatively.

23 experts contributed to foresight analysis, including forecasting trends, refining conclusions, and developing recommendations.

Authors of the study: Vlada Baranova, Maria Bunina, Maria Vasilevskaya, Daria Rud, Anna Kalinina, Yulia Kuzevanova, Yakov Lurie, Nadia Polikarpova, as well as Elena, Anna, and Marina, who chose not to publish their surnames for security reasons.

Text: Maria Bunina, Maria Vasilevskaya, Daria Rud, Yulia Kuzevanova, Yakov Lurie, Anna, and Marina. Editing: Maria Vasilevskaya. Layout: Yulia Kuzevanova.

We express our deep gratitude to all respondents who entrusted us with their stories and took the time to validate the findings and quotations presented in the text. The insights we offer here are meaningful only thanks to the ongoing work that activists continue to carry out despite the risks and precarity they face.

We also thank the participants in our expert discussions and foresight sessions: Sevil Huseynova, Alexandra Baeva, Boris Grozovsky, Gaëlle le Pavic, Alexander Polivanov, Anahit Mkrtchyan, Viktor Voronkov, Grigory Yudin, Irina N., Tatsiana Ch., Dmitriy Oparin, Lauren McCarthy, Valerie Sperling, Viktor Muchnik, Elena Rusakova, and all other experts who chose to remain anonymous.

We are also grateful to the OVD-Info volunteers for their invaluable help in transcribing hundreds of hours of interviews and for their support with editing, design, and development: Ivan Beňovič, Si Mu, Arina Ka, Alina F., Dasha M., Mikhail V., Evgeniya, Assa Bismuth, Yana Vasileva, Darya S., Polina L., and everyone else who preferred to remain anonymous.

why did we conduct this study

A strong civil society is considered key to modern democracies. Since the early 1990s, civil society institutions and practices have emerged in Russia through the efforts of experts and donors (Evans et al. 2006). Despite increasing pressure from the state and low levels of politicization among Russians, many civil institutions have operated for decades, supporting democratic practices “from below” (Chebankova 2013; Morris et al. 2023) and using new formats, tools, and technologies despite pressure “from above” (Shvedov et al. 2022). However, Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine has significantly and dramatically changed the work of Russian civil society, creating and exacerbating a range of threats and vulnerabilities (Gretskiy 2023).

-

In Russia, legislation is changing and repression is increasing. This directly affects the work of initiatives and organizations. For example, bans are imposed on various activities and funding, publicity is restricted, and harassment of both individuals and associations is implemented;

-

The decline in prosecutions for anti-war views indirectly suggests a decline in the effectiveness of public protest as a tool;

-

War divides and polarizes societies. It also creates new vulnerable groups and increases social, regional, and ethnic inequalities;

-

Society's tolerance of violence, corruption, repression, and low living standards is growing.

-

In environments of censorship, the “patriotic” identity constructed by the state receives the broadest and most unrestricted representation.

-

A growing gap is emerging between those who left and those who stayed. This gap is informational, visa-related, financial, and, gradually, cultural. It complicates understanding and dialogue. Emigrants trust other emigrants above all, while trust in remaining Russians is gradually decreasing.

Can civil society in Russia today resist and achieve social change? What has Russian civil society learned over the past 30 years, and how does this knowledge help today? What will Russian civil society look like in 2024? What potential does it have, and what support does it need?

To answer these questions and draw the most complete and up-to-date map of active and potential civil society communities and initiatives in Russia, understand their most pressing problems and risks, identify their strengths, and determine the range of demands they have of each other, allies, and donors inside and outside Russia, we conducted a research based on field data.

theoretical background

the concept of civil society

In defining civil society for this study, we chose not to equate it with democratization—specifically, the ability to participate in politics, form trade unions, or create political parties. Although these features are often linked with civil society in both research and practice, several contemporary studies argue that such definitions are overly normative and do not apply well across different contexts. Agreeing with these critiques, we have adopted a different starting point for studying civil society: solidarity, along with support for human rights, other living beings, and the environment (Alexander 1999).

Unlike other phenomena, solidarity can also take place in extremely hostile environments, such as Russia's, where people lack access to rights, freedoms and resources. It is solidarity practices that allow people to come together for collective action and civic engagement (Ekman et al. 2016). The initial set of tools for researching grassroots forms of solidarity in the Russian context is presented in the works of Karine Clément (Clément 2015). She analyzes how ordinary, non-activist people can change their habits and start participating in collective action through appropriating a part of the common space outside of home or work, as well as through talking about the experience of self-organization.

As a result, we used the following working definition of civil society, according to which we draw the boundaries of the field we studied.

Civil society comprises a set of initiatives whose participants:

-

show solidarity;

-

seek to improve living conditions, protect rights and freedoms, restore justice and political expression, bring about social and political change, realize the will of citizens, voice social problems at the public level and attract maximum attention to them, and create counter-discourses that do not coincide with the state’s official agenda;

-

can use the resources of the state, businesses, and other agents if they set their own objectives, not “top-down” ones, and do not pursue the goal of gaining direct political power;

-

are involved in both grassroots and professional forms of organization—ranging from local chat rooms and one-person expert initiatives to large non-government organizations (NGOs) and foundations—and are most often associated with horizontal governance practices.

Solidarity can be interpreted and used in different ways. Our respondents overwhelmingly share a similar understanding of solidarity: they speak of creative, rather than destructive, collective action.

Here and below, quotes from interviews with respondents are given in italics.

«The energy of civil society is not at all... It is very creative <...> Of course, there are some groups where hatred is prevalent, but these people usually don't unite, so they don't become a political force. People most likely unite on positive ideas, even if they have suffered themselves»

Solidarity is important not as an abstract value or philosophical concept, but as a practice involving collaboration, mutual support, and assistance. In modern humanistic society, we can certainly observe many examples of people coming together to help. One example is when people help those with whom they have a positive emotional relationship, such as extended family or friends. This is called affective solidarity. Another example is conventional solidarity, which is based on the awareness of shared interests and common tasks, values, and traditions (e.g., neighbors uniting for home improvement or wives of mobilized men organizing to protect their rights).

In regard to the relationship between a developed civil society and democratization, as well as the conceptualization of the so-called “uncivil society”—anti-democratic initiatives that some studies include in the definition of civil society and others exclude—a closer look at the third type of solidarity may help clarify these issues.

Reflexive solidarity (Dean 1995) toward the Other—social groups that practice different approaches and share different values—should be emphasized. This type of solidarity involves helping those who do not belong to one’s own community and with whom they do not have emotional and familial ties or shared obligations. Moreover, differences and disagreements become the basis and fuel of such solidarity. When one consciously transcends the friend-or-foe boundary, disagreements lose their disintegrating character and instead become a characteristic of the connections between people.

tree

rhizome

russian civil society as a rhizome

We believe it is productive to examine Russian civil society through the lens of Gilles Deleuze's metaphor of a “rhizome.” Unlike tree-like structures, a rhizome has no single center, size, shape, or direction of growth. Its individual parts can emerge and disappear, and the connections between them are not subject to a single order. All actors of civil society—from individuals to large projects—have autonomy and their own goals, yet they are connected by a shared environment. This is particularly true in Russia, where civil society largely operates “underground” today.

To effectively support the “rhizome,” it is necessary to abandon the concepts of centralization, consolidation, and unification, as well as the search for single solutions. Instead, we must work to find distributed and sustainable strategies that support diversity, autonomy, and opportunities for initiatives to accept assistance while retaining their subjectivity and ability to make independent decisions and respond quickly to changes in the environment.

data and methods

The study consists of four blocks:

-

In-depth interviews: interviews with representatives of communities and initiatives (115);

-

Ethnographic observation of digital communities (12) and of online and offline conferences involving civil society initiatives (8);

-

The quantitative block involves analyzing the connectivity and characteristics of digital civil society communities on VK (5,434) and Telegram (1,062);

-

The prognostic block includes foresight groups with Russian and international experts to validate the research conclusions, forecast the development of the situation and formulate recommendations.

On the one hand, we aimed to map the entire sphere of civil society in Russia, rather than limiting ourselves to our own “bubble.” On the other hand, it was important for us to hear and convey the voices of individuals and initiatives, keep the focus on specific cases and practices, and study the situation at the micro level. Combining these two approaches—the general and the particular—required mixed methods. Quantitative data and analytical methods allowed us to examine the communities and initiatives of interest in terms of general patterns and connections. Qualitative materials from interviews and ethnography enabled us to interpret the statistics, flesh out the specifics, and avoid overlooking diversity and internal contradictions.

For us, it is essential that the three research blocks—the in-depth interview, quantitative, and ethnographic—exist in dialogue with each other. The research design implies constant exchange of materials, ideas, observations, concepts, data, and tools between the researchers to synchronize and enrich the three methodologies. This allows us to constantly sharpen the research focus and adapt methods during the data collection process. For example, the research team obtained access to digital communities for a consequential ethnographic study through initial interviews with experts about the field as a whole. Conducting digital ethnography enabled the generation of more specific and precise interview questions for community participants. Keywords and filtering criteria were then selected from the interview and ethnography data, as well as analysis categories for the quantitative study.

The foresight bloc is unique in that, at this stage, we did not collect field data; rather, we only discussed our findings with experts. Nevertheless, in addition to its main goal of trying to predict the future and understand how to work with it, this stage allowed us to enrich our understanding of the field and better position our conclusions.

qualitative data

Data Collection Method

In our case, the qualitative part involved conducting a large number of in-depth interviews (N = 115). We organized the collection into two stages so that we could analyze the material from each stage and more precisely define the criteria for the next stage.

The preliminary qualitative stage included fifteen interviews with Russian experts deeply immersed in the work of civil society (e.g., media, education, philanthropy, and activism, often in several fields simultaneously), who were willing to discuss their work and civil society in general. We asked them about their observations of the field, the dynamics of recent years, and the challenges and resources they had encountered. We also asked them about the areas of work and specific initiatives and their communities, including its activities and existing partnerships and interactions within the field. During the interviews, we followed the respondents' understanding of which issues were important to them. In this sense, the interviews were closer to unstructured interviews than structured ones.

Based on these initial interviews, we developed working definitions of “civil society” and other relevant concepts. We also formulated hypotheses, adjusted research questions, outlined further sampling, and created a guide for semi-structured interviews. Phase 2 interviews (N = 100) lasted between one and three hours. They included questions about the initiatives' objectives, goals, teams, practices, resources, challenges, victories, inquiries, and interactions, as well as the respondents' professional journeys. Most interviews were conducted online, though some took place offline.

Of the 115 interviews, 114 were audio-recorded and transcribed, and one was received in writing. The transcripts were then coded and analyzed. Code development and interpretation were conducted collaboratively and iteratively.

To uphold the principle of confidentiality, we anonymized all quoted material in the final text. Before each interview, participants were informed that they could choose not to answer any uncomfortable questions and that they could pause or end the interview at any time.

We conducted digital ethnography in both public and closed communities. In public communities, we downloaded messages from the past year and coded the data manually. In closed communities, we informed participants about our research goals and requested access to conduct observations. To prioritize the safety and comfort of activists, we refrained from taking photographs or making video recordings during our participation in communities, conferences, and online events. Instead, we kept ethnographic diaries in the form of written and audio notes, which we later reviewed and discussed within the research team.

Sampling

When selecting initiatives for interviews, we were guided by three principles: first, diversity of fields of activity; second, regional diversity, including non-metropolitan areas (only about 20% of the initiatives we reviewed were from Moscow and St. Petersburg); and third, diversity in the form, scale, and age of organizations. These principles, along with the commissioning parties' and the research team's applied objectives and shared values, helped us identify, select, and prioritize interviewees and communities for digital ethnography.

Similarly, when selecting experts for the foresight analysis, we prioritized diversity. On the one hand, we sought individuals deeply immersed in Russian civil society with many years of experience in practice or research. On the other hand, we looked for experts who had not worked specifically in the Russian context, but who could share their experiences working in authoritarian regimes, polarized societies, or contexts of military conflict.

Among our 115 respondents, a notable number are labeled by the Russian government as “foreign agents” (14) or are affiliated with “undesirable organizations” (3), including two respondents who are both foreign agents and members of such organizations. In contrast, there are virtually no participants who actively cooperate with the Russian state or support its official political agenda. This composition reflects the nature of our applied research and the limitations of our available resources.

All the organizations we spoke with operate within Russia and primarily focus their efforts inside the country, even when some team members are based abroad. Initiatives targeting exclusively Russian emigrant communities were not examined in the study. However, we conducted participant observations of both domestic and international events, including those addressing Russian issues and Russian–Ukrainian dialogue.

Areas of Work. What spheres does the civil society that we researched through interviews and observation operate in?

-

Political Activism and Human Rights Advocacy: Supporting political prisoners and the politically persecuted; working with information and memory of political repression; and electoral rights.

-

Anti-War Activism and Addressing the Consequences of War: Aiding conscripts and conscientious objectors; assisting refugees and individuals with PTSD; countering propaganda and war rhetoric; and grassroots humanitarian aid efforts for the military.

-

Feminism and Reproductive and Sexual Rights: Supporting LGBTQ+ community and fighting for their rights; women's reproductive rights and safety; assisting survivors of sexualized and other violence; and shelters, evacuation, and assistance for women and LGBTQ+ individuals in the North Caucasus republics.

-

Health and the Healthcare Environment; Rights to Health: Volunteering in hospitals; psychological care projects; physical and psychological rehabilitation; prevention, education, and medication for HIV/AIDS; and harm reduction programs.

-

Vulnerable Groups: Protecting the rights of migrant workers and other migrants; helping children with a migration background; providing aid to homeless people; coordination of care for elders, supporting adults and children with disabilities, providing security for marginalized groups (e.g. survivors of sex trafficking and prostitution).

-

Childhood, Family, Care and Growing Up: Support for families in crisis, orphans, parents in vulnerable situations; advocating for changes in family and care legislation; volunteering in orphanages and boarding schools; psychological support for adolescents.

-

Education and Outreach: Educational projects; cultural and contemporary art centers; independent bookstores and other “third places”—venues for lectures, dialogue and debate.

-

Independent Media: Media outlets with varying target audience and scales of operation.

-

Cultural, Local and Linguistic Activism: Preservation of cultural and historical heritage; support for local activists and artists; small-area development and local identity; cultural entrepreneurship; language courses and minority language development.

-

Self-Governance and Support for Professional Rights: Trade unions; elements of local self-governance.

-

Environmentalism: Environmental defense; environmental justice; environmental education, local identity development through environmental work; animal welfare.

-

Support for Civil Society: Infrastructural support; psychological assistance for activists; organization of schools and courses; educational events and retreats for activists; resource centers for NGOs; educational support for those involved in civil society initiatives.

Geography. Russia has a high level of social and regional inequality: financial, educational and other resources are concentrated primarily in the capital and other large cities. Had we aimed for quantitative representativeness, our sample would have consisted primarily of projects based in Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Novosibirsk, and a few other resource centers. However,we designed the project around the principles of diversity and applied relevance, prioritizing initiatives that are more vulnerable and whose voices are less prominent in the broader civic landscape.

Organization. Our goal was to reflect a broad range of organizational characteristics, including scale, longevity, coordination styles, and levels of institutionalization. Our sample includes large, long-established organizations with numerous permanent staff and volunteers with their “classic” hierarchical governance structures. It also includes initiatives that emphasize horizontal structures and practice collective decision-making. Many of these initiatives are relatively new, having emerged in the past few years. Some are small, grassroots activist communities. We interviewed several solo initiatives—projects led by one or two individuals who primarily work alone but occasionally receive support from professional and volunteer networks. Many respondents balance multiple professional identities and types of employment.

Shift in Focus. Given the goals of our research, which were to highlight the most urgent problems, risks, and needs facing civil society, we intentionally shifted our focus away from large, stable, highly institutionalized NGOs. Instead, we aimed to capture the voices of the more vulnerable and younger segments of Russian civil society. At the same time, we see our research mission as illuminating the relationship between the various generations of initiatives. Promoting interaction between these groups is one of our key priorities for developing civil society.

quantitative data

We analyzed a continuous dataset of VK groups and public communities, as well as Telegram chats, that we found through APIs and that met the criteria formulated in several iterations.

Search Stage. In order to search for relevant communities, we generated a closed list of keywords based on the results of digital ethnography of startup communities, as well as internal recommendations of social networks. For each keyword, we collected the first N=100 communities (most likely the most active and/or popular) and assessed whether these were indeed communities related to civil society initiatives; if not, we refined and reformulated the queries. As a result, we settled on the following 56 keywords for which a significant proportion of the first N=100 communities appeared to be appropriate:

-

aid to the front (pomoshch frontu)

-

aid to the mobilized (pomoshch mobilizovannym)

-

animal volunteers (zoovolontyory)

-

animal welfare (pomoshch zhivotnym)

-

assistance to the elderly (pomoshch pozhilym)

-

camouflage nets (maskirovochnye seti)

-

charitable foundation (blagotvoritel'nyj fond)

-

child support (pomoshch detyam)

-

civic activists (grazhdanskie aktivisty)

-

civil society (grazhdanskoe obshchestvo)

-

combat assistance (pomoshch bojtsam)

-

concerned people (neravnodushnye lyudi)

-

creative space (tvorcheskoe prostranstvo)

-

creative workshop (tvorcheskaya masterskaya)

-

crisis assistance (krizisnaya pomoshch)

-

crisis center (krizisnyj tsentr)

-

difficult life situation (trudnaya zhiznennaya situatsiya)

-

disability assistance (pomoshch invalidam)

-

domestic violence (domashnee nasilie)

-

drug addicts (narkozavisimye)

-

emergency accommodation (ekstrennoe razmeshchenie)

-

environmental problems (ekologicheskie problemy)

-

environmental protection (zashchita okruzhayushchej sredy)

-

family development center (tsentr razvitiya semyi)

-

farmer (fermer)

-

feminism (feminizm)

-

feminist (feministskaya)

-

fight against corruption (bor'ba s korruptsiej)

-

helpline (telefon doveriya)

-

historic preservation (zashchita istoricheskogo naslediya)

-

hiv/aids (vich/spid)

-

homeless assistance (pomoshch bezdomnym)

-

homeless assistance (pomoshch bezdomnym lyudyam)

-

human rights defense (pravozashchita

-

human rights project (pravozashchitnyj proekt)

-

humanitarian aid (gumanitarnaya pomoshch')

-

humanitarian mission (gumanitarnaya missiya)

-

initiative group (iniciativnaya gruppa)

-

large families (mnogodetnye semyi)

-

lonely old people (odinokie stariki)

-

low-income families (maloimushchie semyi)

-

maternity support (podderzhka materinstva)

-

migrant children (deti migrantov)

-

nature protection (zashchita prirody)

-

NPO (NKO)

-

non-profit organization (nekommercheskaya organizatsiya)

-

orphans (deti-siroty)

-

palliative care (palliativnaya pomoshch)

-

participants of war (uchastniki svo)

-

political education (politicheskoe prosveshchenie)

-

public association (obshchestvennoe obyedinenie)

-

racism (rasizm)

-

rehabilitation (reabilitatsiya)

-

refugees (bezhentsy)

-

resource center (resursnyj tsentr)

-

sexual violence (seksual'noe nasilie)

-

sexualized violence (seksualizirovannoe nasilie)

-

social and political movement (obshchestvenno-politicheskoe dvizhenie)

-

social assistance service (sotsial'naya sluzhba pomoshchi)

-

social justice (sotsial'naya spravedlivost')

-

social service (sotsial'noe sluzhenie)

-

soldier assistance (pomoshch soldatam)

-

strong rear (sil'nyj tyl)

-

support group (gruppa podderzhki)

-

trade union (profsoyuz)

-

trucker (dal'nobojshchik)

-

victim assistance (pomoshch zhertvam nasiliya)

-

volunteer (volontyor)

-

vulnerable populations (nezashchishchennye sloi naseleniya)

-

vulnerable position (uyazvimoe polozhenie)

-

veterans' assistance (pomoshch veteranam)

-

women's aid (pomoshch zhenshchinam)

-

youth movement (molodezhnoe dvizhenie)

The process of using the API to search for communities by keyword differed between VK and Telegram.

VK'sAPI standard allowsone to download up to 1000 communities by keyword. In the vast majority of cases, this limit was not reached for our keywords. The API also implements full-fledged search algorithms and allows selecting communities. In contrast, the Telegram API limits search results to a few dozen and mostly returns Telegram channels rather than chats. In our research, however, it was the group interactions within chats that were important, including those that function as comment sections under channel posts. We supplemented the standard API output with data from the TG Stat catalog. As a result, we collected N=48,826 communities (groups and public communities) for VK and N=3,877 communities (individual chats or chats linked to channels) from Telegram.

The following limitations are present in the data based on the results of the community search:

-

The data represent the results of search algorithms (either by the social network itself or by the moderators of the TG Stat database); these algorithms are not transparent, and we cannot assess their completeness. At the same time, it is important to note that a “standard user” of a social network, wishing to find a community of interest, is under the same or greater restrictions; that is, these restrictions are coherent to all other cases of social network use.

-

The social network APIs we used also impose a limit on the number of results that can be returned. According to our observations, the most active and/or popular communities tend to appear at the top of VK's search results, while the inactive or irrelevant ones appear toward the end. In most cases, the total number of communities was below the maximum limit. When it was not, we applied additional filtering to exclude the last dozen results. There were fewer communities accessible via the Telegram API, but supplementing the dataset with TG Stat data mitigated this limitation.

Filtering stage. After collecting the identifiers of the communities of interest on Telegram and VK, we moved on to the filtering process. This included two stages: technical and thematic.

It's important to note that Telegram and VK have significant differences in usage scenarios, audience characteristics, and how bots, advertising, and marketing functions are integrated. Telegram tends to have less advertising “noise” and more “organic content.” However, communication often occurs in closed groups. Consequently, communities collected using the same keywords on different platforms require different filtering approaches. To develop technical filtering algorithms, we relied on a team member's expertise in digital marketing research.

In the technical stage, we excluded communities that met the following criteria:

-

No activity within the last month (as of the most recent data download for the study);

-

In the case of VK: no growth of at least 5 participants over the past six months, or fewer than 1% reactions to posts during that same period. Such VK communities are considered “inanimate”: their activity is either the result of random bot actions or is artificially maintained by administrators for reporting purposes or appearances.

For the remaining communities, we collected the following data:

-

Community description;

-

Pinned messages (for Telegram);

-

Description of the linked channel, if applicable (for Telegram).

We conducted thematic screening of the communities using this data. To accomplish this, we developed a rule-based system that defined the criteria for including a community in the research field. These rules considered variables such as community goals, organizational practices, communication topics, the presence of calls to action, fundraising, rhetorical.

Examples of such rules include:

-

“The primary purpose of the community should not be commercial. If the community is commercialized, there should also be evidence of the free provision of help and support and solidarity.”

-

“If the community is horizontally organized and coordinates work on vulnerable groups, then it fits.”

-

“If the community's main focus is entertainment and resembles a personal blog, then it's not a good fit.”

To operationalize these variables, we submitted targeted queries to GPT-4o and asked the model to estimate the probability that each variable would be present in a given message. For instance, the probability of the variable “funding: government funding” would be 1 for a state-run social services center and 0 for an anarchist chat. When the information was insufficient, the model returned a value of -1. We accessed GPT-4o via the OpenAI API and built a custom library for integration. Alongside specific variable queries, we provided a system prompt that included a brief overview of the research objectives. We ensured quality control of the neural network’s output using metrics of completeness and accuracy on test samples (N=20 for each keyword, totaling N=1,080). In these samples, all borderline cases were marked with -1 to allow for later manual review.

We applied deterministic filtering rules to the model's output based on the above-described rule set to determine if a community met the inclusion criteria. Communities that did not meet any criteria were flagged for manual validation.

Through this process, supplemented by a manual review of ambiguous cases, we identified 5,434 communities on VK and 1,062 communities on Telegram.

Classification stage. To identify interesting trends in community data, we used neural networks to categorize the remaining communities further. We downloaded 500 recent chat messages for Telegram and up to 20 posts and 200 comments from the last 2 months for VK. Then, we composed additional queries to GPT-4o using the same methodology. We were interested in:

-

Areas of civic engagement represented in the community;

-

Organizational practices;

-

Geographic reference;

-

Clarification of the narratives from the previous step.

Analysis Phase. One of the key components of our quantitative data analysis was constructing a community connectivity graph based on shared participants. We collected lists of VK community members who had published posts or comments within the last 500 posts in each community. We also collected the authors of the last 10,000 messages in the selected Telegram chats.

Next, we tested different algorithms for creating connectivity graphs. Among other things, we experimented with different thresholds for determining connections between communities: These included 1%, 3%, and 5% of total members, as well as minimum shared user thresholds of 2, 5, 10, or more. These thresholds were necessary because despite all previous filtering, bots were still present in some communities.

After creating the graphs and color coding the vertices according to thematic categories, such as activity topic, geography, narratives, sources of funding, and organizing practices, we developed hypotheses about the relationships between different community characteristics. We then tested these hypotheses using simple correlation analysis.

foresight analysis

Composition and Characteristics of Expert Groups

The foresight sessions were the final phase of the project, linking our findings and conclusions directly to the main practical objective of the study as a whole.

It was important to us to make sure that the trends and recommendations we identified for donors would be correct and relevant in the months following the completion of the study. To do this, we invited experts to “predict the future” based on our data.

In the foresight analysis, we brought together several types of experts:

-

Russian specialists with academic background, practical experience in media or civil society initiatives in emigration or within Russia;

-

Foreign (English- and Russian-speaking) specialists on the history of Russian civil society;

-

English-speaking practitioners from the world of peacebuilding;

-

Foreign (English- and Russian-speaking) specialists with academic background, practical experience in media or civil society initiatives in authoritarian countries with similar contexts (e.g. Belarus and Azerbaijan).

A total of 23 experts took part in the foresight sessions. Sixteen joined the Russian-language sessions and seven took part in English-language sessions.

Our criteria for selecting participants were as follows:

-

Relevant experience in studying or developing civil society initiatives in Russia and others contexts marked by repression, military conflict and divided societies, or specialists in Russian studies;

-

A solid reputation and commitment to ethical research and activist principles, such as reflexivity, non-harm, non-violence, and intersectionality;

-

If the first two conditions were met, we would also ensure that an expert had a meta-perspective and was able not to focus on one specific initiative. Additionally, the respondent must not be on our list during the fieldwork phase.

The groups were divided by language based on the participants' preferences. To encourage diverse perspectives, we brought together people with different backgrounds and approaches to civil society, combining practitioners and theorists in each group. This ensured that discussions reflected a wide range of perspectives and that participants' ideas were immediately tested against the group’s collective experience.

Methodologically, our work with Russian and Russian-speaking experts was similar to our work with English-speaking experts. However, when necessary, we provided foreign participants with additional context to help them understand Russian civil society. During discussions and forecasting, the participants often drew on analogies from their own experiences or from the communities they had studied—those whose Russian counterparts they were analyzing. This approach provided us with a broader and more nuanced understanding of the current dynamics and potential trajectories of the observed trends.

We discussed the issue of anonymizing the experts in advance, both during their participation in the sessions and in subsequent mentions in the project materials.

Methodology

To conduct foresight sessions, we analyzed more than ten most commonly used approaches and methods and decided to apply a dynamic SWOT analysis.

Based on our research, we have formed a definition of civil society and identified desirable directions for its development. We have also determined the current state of

SWOT variables. We obtained the following matrix:

S[trengths]: internal resources of civil society organizations

W[eaknesses]: internal problems of civil society

O[pportunities]: external opportunities for civil society (according to our respondents)

T[hreats]: external risks to civil society (also according to our respondents)

After obtaining consent from each invited participant, we sent them a short brochure outlining these factors and providing recommendations for donors interested in supporting Russian civil society.

It is important to note that we did not study external factors directly, but rather examined their impact on civil society. Therefore, it was crucial to include experts specializing in macro-level factors within authoritarian contexts (from fields such as political science, economics, and human rights) in the sessions. We believe their expertise helped the group contextualize and deepen its understanding and analysis.

Each foresight session lasted between 1.5 and 2.5 hours, and each group included 2 to 4 participants.

We invited experts to engage in dynamic SWOT forecasting, structured as follows:

First, OT in Dynamics: Participants were asked to generate possible external scenarios (opportunities and threats) for 2025 and estimate their likelihood. To guide this process, we proposed some recommendations from the study as examples of potential opportunities. For example: “Activists will be able to receive personal stipends from donors equivalent to the minimum wage.”

Then, SW in Dynamics: Participants were asked to evaluate potential internal scenarios (strengths and weaknesses) and propose strategic responses from civil society based on the likelihood of various OT scenarios occurring. For example: “Donors stop funding free meetings/retreats for initiatives,” or “VPN use becomes criminalized,” followed by guiding questions such as “What are the risks to civil society development in this situation?” and “How can we adapt to this situation?”

After the sessions were completed, we summarized the forecasts and conclusions provided by the various expert groups. Based on these insights, we revised and refined our recommendations for donors, which are included in this report.

detailed findings

map of russian civil society at the end of 2024

Through a visual analysis of community graphs in social networks and data from expert interviews, we identified six main clusters of civic activity. We then described these clusters in detail based on interview and observation data.

Explicitly Anti-war and pro-democracy activism; major media, investigators, and researchers; human rights movements (including women’s and LGBTQ+ rights); and assistance to Ukrainian citizens

These initiatives often relocate, hybridize, and/or operate clandestinely or anonymously. While they generally have sufficient resources, they may lack dialogue with a broader range of grassroots initiatives. They may not demonstrate “victories” in the traditional sense, such as influencing government decisions, because the state is committed to their suppression. Many of these initiatives avoid interaction with the state, although there are exceptions, such as ongoing dialogue about issues like torture and detention conditions in colonies.

Environmental and urban defense, decolonial movements, defense of social and collective rights, leftist movements, trade unions and professional associations, local initiatives, and local media

These actors historically have limited ties to the first group. The two clusters often struggle to find common ground, due in part to the centralization and stark inequalities within Russia. The first group tends to be associated with capital cities, while the second is more prevalent in non-capital regions and smaller towns. These initiatives typically lack resources, visibility, and broad social connections. Although often perceived as “non-political,” they are in fact politically active, and sometimes adopt apolitical positioning strategically to improve their survival prospects. They operate under constant threat of repression, observe various secrecy practices, and face acute issues of burnout.

Assistance to people in vulnerable situations, marginalized groups, and the broader charity sphere

The state actively encroaches upon this space, seeking to seize its agenda. In response, initiatives employ various strategies. Some engage in confrontation with the state regarding issues such as reproductive rights and motherhood, while others adopt mimicry in areas such as healthcare. The first group and other independent actors often quietly and discreetly seek support and alternative funding models, especially under the constraints of sanctions and repression. Many also face significant shortages of resources and technological capacity.

Animal welfare

Of all the visible and interconnected sectors, this is the largest and fastest-growing area of independent, horizontal activity. Currently, participation here represents a relatively safe space for practicing values such as solidarity, empathy, and justice, specifically in relation to animals. Participants tend not to form NGOs or formal organizations, but they often go beyond atomization in search of allies and collaborate with people with whom they may disagree in order to achieve a shared goal.

Third places, centers for building and maintaining horizontal ties

These spaces function as semi-public places that resemble the “dissident kitchens” of the USSR era. Unlike in the past, however, these spaces are more accessible to new participants. As of 2024,, they were successfully fending off pressure from pro-state actors by translating conflicts into bureaucratic or administrative terms. These venues serve as entry points for new participants and as support spaces for activists who have lost previous opportunities for civic engagement due to repression or exhaustion.

“Uncivil society”: wives of mobilized men, support groups for Russian military personnel, those who produce camouflage nets (setkoplyoty), right-wing activists, and pro-state initiatives across various topics

The state uses grassroots and professional activism in these initiatives to normalize war and repression. However, these groups are not immune to repression themselves. In some cases, initially pro-state or neutral actors become politicized. They differ structurally and ideologically from other civil society groups, warranting further study. These initiatives compete with civil society for volunteers and humanitarian agendas and possess latent protest potential.

You can learn more about the contours of civic activism clusters in Russia, as well as the connections between them, using the interactive graph of online civil society communities on this page.

.jpg)

When evaluating the significance of a topic within a sector, it is helpful to consider not only its quantitative representation, but also its capacity to bring people together and engage them in broader civil society activities. To measure this, we calculated—for each topic—the average number of neighboring communities. The resulting distribution graph is presented below.

.jpg)

What we observe is that topics more closely tied to reflexive solidarity—such as supporting vulnerable groups, anti-war activism, human rights, and animal protection—are more effective at uniting people than more widely represented and safer themes like childhood, healthcare, and education, or even support for the front. This ability to form connections can serve as an indicator of how grassroots a movement is. When a community has many connections, it suggests that various initiatives emerged independently and formed links later on. In contrast, top-down or centrally coordinated communities tend to have fewer connections.

Taken together, the data from the distribution and connectivity graphs indicates that animal protection is one of the most promising areas for further observation. It is one of the top five most popular topics on both social networks and is highly connected, particularly on VK, where it holds the record for the most internal links among communities.

Another topic of interest is ecology. Although ecology is underrepresented on both VK and Telegram, our qualitative data shows that initiatives related to ecology tend to follow strict digital security practices and primarily communicate through secure messengers. This likely explains why they are not more visible in the public digital space.

The charts below show the distribution of connections between communities organized by topic, providing a quantitative view of what is also visually observable in the connectivity graph.

We see that initiatives in the social sphere, such as those related to family and childhood, healthcare, and education, are generally well-connected internally. However, they remain distant from more politically sensitive areas, such as anti-war activism, political mobilization, support for vulnerable populations, and animal protection.

The human rights and independent journalism sectors play a key role in connecting otherwise separate areas, especially on Telegram. However, these sectors are less connected to ecology and collective rights. This can be explained by their differing ideological orientations: Many human rights and media projects lean more neoliberal, while ecological and social justice movements, particularly those outside capital cities, tend to lean more leftist.

analyzing the digital footprints of civil society work

themes of work in communities

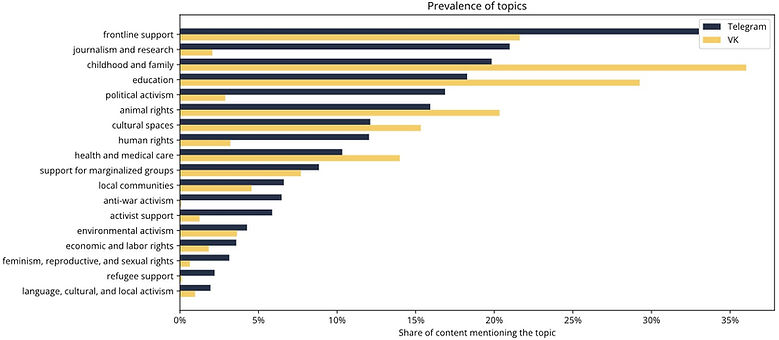

In contexts where there is low trust in survey data, such as in authoritarian regimes, social media data can serve as a partial substitute for the quantitative monitoring of civil society dynamics. One key question is what topics civil society is engaging with and how these topics are distributed. The graph below attempts to answer these questions, albeit only partially.

At first glance, the graph suggests that the largest part of Russian civil society consists of “uncivil society” actors, or those who provide grassroots support for the Russian military. In contrast, far fewer people appear to be involved in anti-war, social, cultural, or environmental activism. However, this interpretation should be approached with caution. The dataset only includes open communities. This means that the visibility of a topic depends not only on its actual prevalence, but also on how safe activists feel discussing it publicly. For this reason, the current data only provides a snapshot. More nuanced and reliable insights will likely emerge as this type of data accumulates over time.

.jpg)

Finally, both frontline aid and animal protection demonstrate what we might call “self-contained” connectivity. They are strongly networked within their respective thematic clusters but have limited connections to other spheres. This suggests that these topics serve as entry points into civil society for many participants.

geographical distribution of communities

Another important aspect to consider is the geographical distribution of civil society activity. In this study, we used Russian-language keywords, which likely caused us to overlook communities operating in other languages. The pie charts below illustrate the distribution of communities in metropolitan and non-metropolitan regions, as well as a more detailed regional breakdown for Telegram and VK.

The data show that, at least when it comes to civil society-related topics, Telegram skews more metropolitan. In contrast, VK has a stronger presence in the Northwestern Federal District, the Volga region, and the Urals.

Despite their geographical differences, metropolitan and non-metropolitan regions share many characteristics. In both areas, communities engage in joint action, practice crowdfunding, foster positive emotions and gratitude toward one another, and criticize the state.

There are also notable distinctions. In non-metropolitan regions, the state is often the sole donor to civil society organizations working in the social sphere. This influences their alignment with state programs.

.jpg)

In contrast, reflexive solidarity—solidarity rooted in ethical reflection and shared values—is more prevalent in metropolitan areas. This disparity can be explained, in part, by socioeconomic inequality. Residents of Moscow and St. Petersburg tend to have more resources to share with others and an easier access to knowledge on philanthropy.

.jpg)

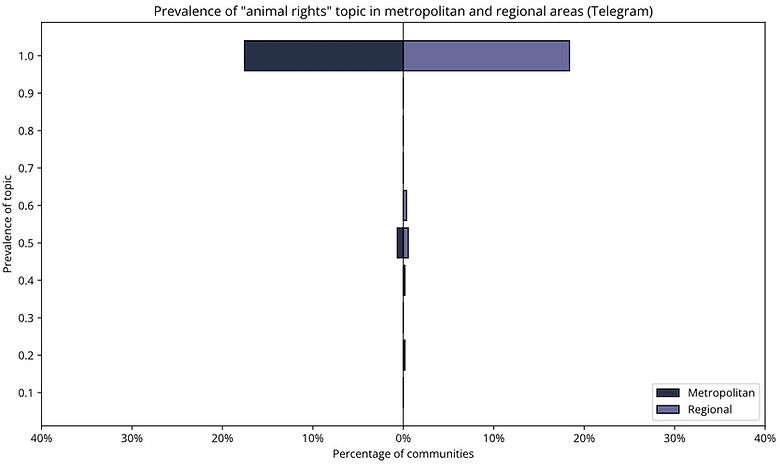

The high prevalence of a culture of solidarity in Moscow and St. Petersburg is also evident in the normalization of human rights discourse within these communities. As the graph below shows, human rights rhetoric appears not only in communities dedicated to human rights, but also in communities with a more general interest. In these communities, human rights content comprises around 80% rather than 100% of the discussion.

.jpg)

Conversely, Z-activism, or pro-military or pro-state grassroots activism, is less prevalent in capital cities, likely due to differences in mobilization policies. Metropolitan areas tend to have fewer conscripts and greater access to legal support and human rights defenders. This also means that grassroots communities in non-metropolitan areas, which are often composed of relatives of mobilized individuals, are more actively involved in supporting the front.

.jpg)

Once again, the animal protection community stands out as being equally well represented in both metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas. This finding reinforces previous observations about the community's exceptional unifying potential across different regions and social environments.

.jpg)

connections between topics, rhetoric and practices

Based on our visual analysis of connectivity graphs—colored according to different variables—we formulated the following hypotheses about communities that practice reflexive solidarity:

-

They are less prone to hierarchical structures, which means there is less of a division between “major” and “minor” participants.

-

They are more likely to unite through shared anger, outrage, and criticism of the status quo and not only positive emotions.

-

They are more closely associated with anti-state themes and critical rhetoric.

Correlation analysis confirms these hypotheses. Specifically, reflexive solidarity tends to emerge in communities that openly condemn war and repression. The analysis also shows a negative correlation with expressed hierarchical roles and a positive correlation with expressions of criticism. At the same time, certain practices, such as calls for joint action, requests for help, and expressions of gratitude, are characteristic of all the communities included in our dataset. This is partly because the presence of collaborative practices was one of the inclusion criteria for a community in the study.

The full correlation matrix of various community characteristics is presented below.

Correlation calculations also reveal the distinct functions and communication cultures of Telegram and VK. Telegram's decentralized communities tend to be anti-state and focused on supporting activists. In contrast, VK has more “governmental” communities, particularly in education. These communities usually do not engage in crowdfunding; rather, they receive funding from the state. Interestingly, they also rarely exhibit internal solidarity, a practice common in nearly all other community types. This lack of solidarity may be due to the fact that many of these groups form around educational institutions, such as discussion clubs or parental communities. Another notable observation is that cultural spaces seldom rely on fundraising. Instead, they tend to use monetization models. Additionally, government funding is more prevalent in non-metropolitan regions, while crowdfunding is more common in metropolitan areas.

the challenge to civil society: political pressure

the price of civic activism

When discussing civil society in contemporary Russia, it is important to recognize the risks associated with nearly any initiative. Traditional forms of political resistance, such as protests, public demonstrations, and openly criticizing the government, have become nearly impossible due to the threat of repression. According to OVD-Info, Russia has enacted 45 repressive laws since the start of the full-scale invasion, and the International Federation for Human Rights has counted 50 such laws between 2018 and 2022.

The repressive machinery now considers virtually any action aimed at developing political agency and horizontal networks to be a potential crime, especially if it could provide an opportunity to criticize the state, highlight social injustices, or defend civil rights. This explains the aggressive stance toward charitable foundations and independent journalism; the state increasingly views these entities as direct competitors or enemies.

Authoritarian regimes use various tools to suppress dissent and political activism. Examples of legal repression include designating organizations or individuals as “undesirable,” “extremist,” or “foreign agents”; initiating criminal proceedings against opposition figures; and prosecuting people for “slander,” “fake news,” or “discrediting the army.”

Receiving one of these hostile designations greatly increases the risk of losing an initiative's audience, funding, partners, and assets.

«Many friends and partners have been labeled “undesirable” and “foreign agents” for a long time. It seems to me that it has become clear that all of this is just theater that can be quickly shut down»

A defining feature of authoritarian contexts is the combination of direct repression, persistent uncertainty, and absence of clear “rules of the game.” People do not know what is permitted, what might be punished, or when arbitrary enforcement might occur (Glasius et al., 2018).

«For example, the last call was about foreign agent books [books written by authors who now have a foreign agent status]. No one could understand what we were supposed to do with them, which plaques to use, who was responsible for what, or what the restrictions were»

The threat of sanctions forces initiatives to forgo potential resources and resort to self-censorship.

«My colleagues, poor people, and I are constantly afraid that we will be declared foreign agents because everyone around us already has been—our whole environment and those from whom we studied <...> Our sphere is not well known in Russia, so private funding is scarce. That's why foreign funding was important to us. We can't use it anymore because there is a huge risk—we have a lot of specialists living in Russia»

Participants in opposition-aligned projects or initiatives that address taboo issues fear infiltration by state agents, including informants and Center for Combating Extremism operatives. The mere presence of such individuals in chat rooms or meetings can have devastating consequences for the organization, including surveillance, administrative and criminal prosecution of participants, especially if they speak freely.

«A lot of people started to recognize us. Recently, many new people started showing up, and we realized that we're done—unsafe and uncool, to put it simply. That's why we decided to go underground again. We've given up public spaces.... We just want to gather in different places all the time so that the enforcers won't come to us anymore. We are also gradually abandoning social networks. We don't announce events anymore. For example, we only invite people through personal invitations or activist group chats, but that happens less frequently because it's not so safe anymore»

«Most of our team is in Russia. We don't want to take any risks. That's why we're taking action—for example, we removed [mentioning] non-binary people. Again, nothing will be done for mentioning them. However, they may pay more attention to us. Some communities and publishers are reposting us, which is drawing attention to us. It is very likely that someone will come in, see the non-binary people, and draw attention to us. This would not be desirable from the perspective of people's safety in Russia who are devoting their time and effort to helping»

As independent structures are being repressed, the state is actively co-opting the nonprofit sector by creating GONGOs (government-organized NGOs) and launching youth engagement programs. As part of its strategy to promote volunteerism, the government aims to engage 45% of Russian youth in state-sponsored civic and volunteer activities by 2030. This initiative is framed as cultivating “patriotic and socially responsible citizens.”

«The thing is, there's now a general trend toward some kind of state control. One way or another, this topic has been taken over to some extent. I mean nonprofit organizations. This is a new reality that everyone is facing now»

In authoritarian conditions, initiatives must be constantly vigilant, closely monitoring the actions of the state and its enablers. They must also make difficult strategic and ethical choices regarding their values, access to resources, and the security of their team and recipients. The collective and familial experience of repression during the USSR also fosters pessimism. As one expert put it, “If this country needs to build a Gulag, it will build a Gulag.”

Nevertheless, it’s important to resist one-sided narratives. State repression, control, and associated risks are not the only context shaping Russian civil society, nor is it a primary one. While civil society actors, donors, journalists, and researchers must acknowledge it, focusing exclusively on total repression can be paralyzing. The emphasis exclusively on danger and decay can overshadow the everyday resilience, successes, and local relevance of civil society work.

According to our data, the most successful and active initiatives are primarily focused on specific local social tasks, despite having to adapt to the ever-changing repressive landscape. These tasks become an expression of their civic mission, responsibility, and political stance, and the initiatives often succeed in addressing them. The narrative of repression, anxiety, and alarmism surrounding the idea of “tightening the screws” can be productive when it motivates mutual aid, solidarity, and the exchange of experiences (e.g., security techniques). However, in other contexts, this narrative can contribute to the counterproductive exoticization of Russia as solely a “scorched field” of FSB agents, torture, and dead hopes.

strategies for initiatives

Many initiatives focus on physical, legal, and digital security practices. They develop their own technologies and frameworks to make surveillance, hacking, and blocking more difficult. However, not all initiatives utilize such developments.

The demand for such technologies stems from two factors: a lack of digital literacy and the constantly shifting landscape of digital services. Maintaining digital operations has become much more difficult due to sanctions and the withdrawal of international companies from the Russian market.

«Apparently, the server we were using has been blocked again. We're moving to another one now. It's always a hassle to make everything work in the office. Plus, some services are stopping working in Russia. We received another letter from Microsoft saying that our organization has been reclassified as undesirable for cooperation. Google sent us a similar letter during the holidays saying they’re going to cut us off too <...> Most organizations like ours [that operate in Russia], of course, have the necessary qualifications. However, there just are not enough services willing to work with NGOs operating in Russia. This includes cloud technologies and AI-related services. Because everything is used via VPN. For example, you have to register with a Serbian phone number. These are the main difficulties»

A high level of digital literacy is essential to improving the security of both employees and beneficiaries. Today, organizations in Russia are advised to verify the servers of the platforms they use, encrypt messengers and devices, set up two-factor authentication and auto-delete messages, and avoid using the same device for work and personal activities. Due to the country's relatively low level of digital literacy, urgent digital education and transforming communication practices have become another challenge for activists. Many projects still do not integrate these practices into their daily operations. As with the uncertain “rules of the game” in an authoritarian regime, digital security practices are similarly fraught with ambiguity. People are rarely certain that the tools they use are completely reliable, and digital infrastructure often proves fragile.

«These are all technical tools that you can never fully trust, especially when working on sensitive topics <...> All these tools are widely used in nonprofit projects in Russia and carry significant risks. There is no universal risk template that fits most organizations because risk assessment and risk management vary greatly from group to group»

The Russian government blocks online access to many resources used by initiatives and individual activists. VPNs are required to access these sites, creating an additional financial burden. Furthermore, purchasing a VPN is not a solution once and for all. They are often blocked as well, and sharing information about functional services is legally restricted, creating further risks. In general, many digital security systems require constant updates and can incur additional costs.

«We’re undergoing another audit and making adjustments to our security system so that we can work productively. Our goal is to bring everyone up to roughly the same level of protection <...> Our goal is to keep the system affordable and prevent it from draining our resources»

With the withdrawal of international companies from the Russian market, NGOs also lost access to key tools for coordination, data storage, and security. Popular platforms like Miro and Notion, often used by distributed teams, have become unavailable—necessitating significant effort to find alternative digital infrastructure.

Cybersecurity problems are especially pronounced in regions where collaborators are often under-resourced and thus at greater risk. Below are observable trends in digital communication practices among the communities we studied, including both large-scale and small, grassroots efforts.

To support initiatives, it might be helpful to do the following:

-

Encourage the exchange of experience, technologies, and practices between the “technological vanguard” and more conventional initiatives. Where in-house development is not feasible, infrastructure for IT, accounting, legal, administrative, marketing, and social media work can be outsourced to more advanced peers.

-

Provide indirect support by covering the cost of task managers, communication tools (like Slack, and AI services, depending on the needs of each initiative).

-

Ensure that international partners adhere to strong security practices, such as protecting sensitive data with robust passwords. At the same time, consult directly with initiatives and their tech-savvy peers to determine which security practices are helpful and which are harmful. Allow Russian organizations to assess the risks of participating in international programs independently and support them through public discussions and legal advice.

Many initiatives critical of the Russian state do not publicly position themselves as political, instead focusing on social, cultural, or charitable work. This strategy often reduces the risk of repression for those seeking to continue their activism. It can be valuable to consider the implicit political content of an initiative, which may align with its core mission even if not outwardly expressed.

Some initiatives employ a “division of labor and risks” strategy. Some team members relocate to another country (or region, if the threat comes from local regional authorities) and engage in public activities there. They have an opportunity to apply for foreign grants. Those remaining in Russia continue on-the-ground work while maintaining anonymity or semi-anonymity. They receive resources from colleagues abroad rather than directly from international donors.

This strategy offers some protection from legal threats and law enforcement attention. It could be further supported by enabling Russian initiatives to publicly report via external representatives so that they are not forced to publish sensitive data that could heighten political risks.

blurring the lines between the state and civil society

Upon closer examination, many initiatives and organizations—especially those engaged in social or cultural work that is not explicitly oppositional—do not fit neatly into the pro- or anti-state binary. The state itself is not monolithic; law enforcement, regional officials, and pro-war activists can act in contradictory ways at different levels of governance. Consequently, the same initiative may receive state funding while justifying its international contacts to law enforcement or opposing local authorities through legal complaints. Therefore, it is more accurate to speak of a diversity of relationships with the state at both the federal and local levels.

Our data supports this heterogeneity, showing that an organization’s decision to interact with the state, and how it does so, depends on the scope and nature of its activities, as well as the political climate in its region. Although most respondents identified the state as an antagonist, approximately half currently use or are considering using its resources as international funding continues to decline.

«Plus we have a hotel. It's a security issue. Generally, we have a private company guarding the first floor, and the Rosgvardiya guarding the second floor. This can be scary for people, especially for activists. Unfortunately, due to corruption and monopolistic schemes, hotels cannot be guarded by anyone other than the Rosgvardiya. We are fine, though. In general, we have not experienced any problems with them»

By 2024, avoiding dependence on the Russian state will be a privilege. Even projects that are not reliant on state funding spend considerable energy following regulations, maintaining relationships with local officials, and avoiding attention. Many of the representatives we interviewed said they “try to do everything right.”

«This year, we received grants from both FPG and the [name of department and city] Department. These are the two largest grants we received at the end of last year. But it's such a crapshoot... I would also be happy to be among those who say, “Oh no, we don't take government money. We don't work with those.” But I'm afraid we have no other option because we can't accept foreign money»

Part of this complicated relationship between initiatives and the state has historical roots. For example, the large, state-run platform Dobro.RF used to be Dobro.Mail.ru, a well-respected organization similar to “Need Help.” With the outbreak of the full-scale invasion, Dobro.RF underwent a de facto takeover. Some staff members left, while others stayed because the workflows did not change overnight. The same applies to volunteers and beneficiaries: some continue their involvement and partnership with Dobro. RF due to their own relationships with specific employees or projects.

This does not apply to openly pro-government initiatives: the overwhelming majority of our respondents reject cooperation with them. The names of the organizers behind such projects are usually unknown to long-time nonprofit professionals, and the volunteers from pro-war chats (“to help the front”) rarely overlap with other civil society audiences. We assume that for many pro-war organizers and participants, this is their first experience with any kind of collective or solidarity-based action—suggesting that until recently, they were entirely disconnected from civil society.

«A new generation has grown up, and I try to follow them as best as I can. The people volunteering to support the front—they are also our colleagues, even if we have certain political differences. I see them go through the same stages we did: first, forming volunteer groups to solve specific problems, then organizing efforts more formally, then tackling infrastructure. But everything is more extreme there—because their problems are more extreme. Their methods are more extreme, too, because many of them are used to organized violence»

Participants in such initiatives are often reluctant to engage in dialogue. Most of the participants in our study who agreed to take part preferred impersonal forms of communication, such as written correspondence or voice messages, and tended to give dry, abstract responses.

Counterintuitive as it may seem, pro-war initiatives also complained about the lack of state support, the hostile atmosphere surrounding their work, and the absence of societal solidarity. This may reflect the state’s general distrust of grassroots initiatives and self-organized efforts, as well as the system's internal chaos and fragmented nature at various levels.

Some pro-war and pro-government initiatives express frustration that they receive little or no institutional support in return for “taking on the work of the state.” Their dissatisfaction is heightened when they face opposition from local officials seeking to monopolize certain types of volunteer work for corrupt purposes or to boost their public image, effectively blocking outsiders from entering those spaces. Some pro-war activists view the “abstract” upper levels of the state (federal government) as more aligned with their values. They see local authorities as self-serving and disconnected from the common good.

Additionally, activists who support the front are better than others at identifying flaws in the system (e.g., noticing that humanitarian aid does not reach its intended recipients or hearing soldiers complain about substandard uniforms). They convert these observations into criticism of certain aspects and practices of the current system, not of the overall state course. Although these observations are made on a small scale, they overlap with PS Lab's study of how Russians perceive war. This study shows at what levels non-opponents of war can criticize certain aspects of the war itself and the government.

Pro-war and pro-state activists and organizations that are “apolitical” also fear reprisals because they feel the cost of criticizing the state is too high and the rules are too uncertain. Even those generally loyal to the state can easily come under pressure if their activities or rhetoric highlight official policy weaknesses or hinder its representatives.

Strategies of Civil Initiatives

The tactics that initiatives use to build relations with the state depend on a number of factors. In some cases, an initiative may demonstrate loyalty and appear to comply with the rules while maintaining its values—in fact, this may help preserve them.

Environmental initiatives, for example, are often forced to adopt an apolitical stance to involve a wider range of people in protests and maintain their advocacy abilities. In other cases, however, we observe co-optation rather than mimicry. For instance, many women's initiatives now conduct anti-abortion campaigns despite previously supporting gender and reproductive rights, due to pressure from the state. Finally, in certain areas, such as education and healthcare, formal compliance with state standards is necessary for an initiative to reach its intended audience.

We recommend assessing the public positioning of an initiative flexibly, in light of its operating context, and distinguishing between reflexive mimicry and coaptation.

If it does not contradict international law, it may be reasonable to consider co-financing with the Russian state or other donors who do not share the initiative's values, if co-financing is the only way for the initiative to survive.

horizontality and chaos as new tools for sustainability

A hierarchy with prominent leaders who have the authority to make final decisions is more characteristic of pre-war or fully relocalized initiatives. These initiatives were able to safely use media resources and build the personal brand of the top manager to attract funding and audiences. Respondents from such organizations may mention the word “horizontality” in interviews without prompting but usually do so with a tone of skepticism or negativity.

«We are not trying to create a horizontal organization or project. Firstly, I think many people don't need it. Secondly, it seems to me that, often, there is still a vertical behind the horizontal; someone still makes the final decision»

Most young organizations practice horizontality to varying degrees, ranging from incorporating elements of collective decision-making to adopting fully networked structures where not all participants know each other. It is important to note that even established organizations undergo transformations in times of crisis. Many begin to introduce elements of horizontality and move away from rigid vertical structures. These changes are often introduced rapidly as a defensive response to state aggression and are also linked to an influx of new, more liberal activists.

.jpg)

The Number of initiatives with elements of Horizontality by year of commencement of work

At the same time, activists may avoid the term “horizontality” and instead use terms such as “collegiality,” “debates,” “colloquiums,” “meetings,” and “organizational meetings.”

«But we also have these pep sessions. Well, “pep sessions” sounds a little weird. It's more like a tea party. We talk about basic things at the communal tea table»

The desire for horizontal structures and networks has a value-based and pragmatic foundation. Though this organizational principle is often criticized for slowing down decision-making, it allows for rapid disbanding and reassembling, role swapping, and avoids rigidity, inertia, and dependency on specific formats, locations, and structures. These qualities make the organization more flexible and “multifaceted,” including legally, and enable a quicker response to emerging challenges. As one interviewee from an environmental initiative that values horizontality said: “I am proud of the fact that we are keeping things chaotic.”

In the current repressive environment, this chaotic nature is especially useful from a security standpoint. Many respondents noted that law enforcement was unable to understand the organizational structure, resulting in the targeting of only public figures or individuals who were more easily identifiable, such as through financial transactions linked to specific organizations.